A Hitchiker´s Guide to Deep Bass

Walk through the rooms of any high-end audio show and listen to the demonstration music that is used to exhibit a system’s bass capabilities, and you will - sooner or later but inevitably - bump into one of the two classics that have acquired a cult status over the years. Listeners are impressed how deep this or that a piece of gear can play, and exhibitors talk about the loudspeaker extension ‘down to 16Hz’. The problem is that such a bass tone is not present on these recordings.

I am not going to discuss the topics that we have chewed over already – and that are extremely important to what the bass is like in a room - like the room size and room acoustics, speakers and woofer arrangements, subwoofer integration, DSP, and Fletcher-Munson equal loudness curves. Instead, I would like to turn your attention to how individual frequencies contribute to what we perceive as the deep, punchy, and accurate bass.

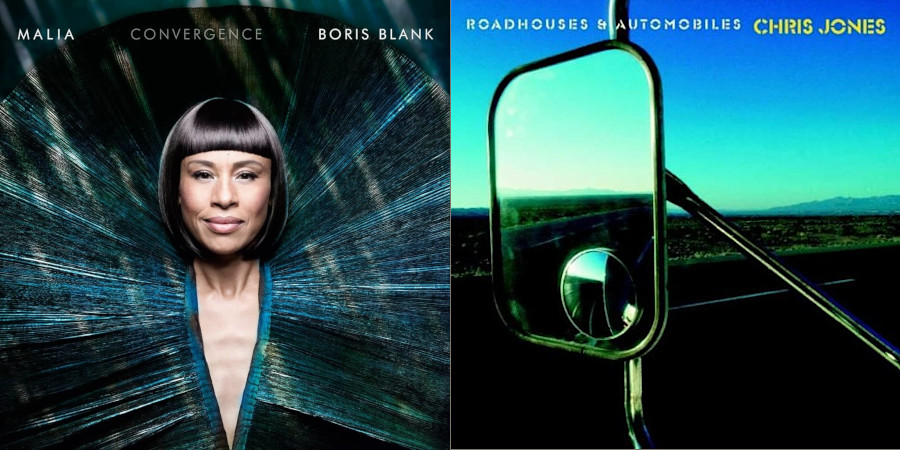

In reality, the non-existence of the subsonic frequencies does not mean that our ears and brain cannot evaluate what we hear as exciting ultra-low bass rumble that creates pressure in your chests and sends shivers down to spine. The two recordings I mentioned are Celestial Echo (Boris Blank and Malia, Convergence, Universal Music), and No Sanctuary Here (Chris Jones, Roadhouses & Automobiles, 2003, Stockfisch Records). The former is a purely electronic piece and the showcase of Blank’s ability to craft breathtaking transparency with bass lines, high lines, and vocals combined. The latter is a blues piece, “authentically recorded” as claimed by Stockfisch records.

Perhaps it was authentically recorded (and it was, although the engineers could avoid the microphone clipping in the vocal track), yet it was heavily equalized in the low-end and post-processed, including quite drastic selective compression at the mastering stage. The guitar is played is in D-major key, the chords used are D-major, D-minor, G-major, and A-minor.

The lowest E-string on a bass guitar is tuned to 41.2Hz. However, the A note has 55.0Hz fundamental frequency, the D has 73.4Hz, and the G has 98.0Hz. Thus, although it is hard to accept, there is no ‘deep’ bass on No Sanctuary Here. It cannot be there and, in real world, anything in the sub-bass region can only be played either by big pipe organs, or synthesizers. It is the combination of mid-bass, upper-bass, and midrange what we perceive as “ultra-deep-low-end” in Chris Jones’ track. Even worse for vinyl masters, where the A-note is about where the high-pass filters are applied to prevent the needle travelling outside the groove.

So why No Sanctuary Here sounds so captivating? The answer lies in skillful equalization and compression, and in the mass of air moved in the studio which has nothing to do with the guitar’s fundamental tones, but which contributes significantly to the sense of expansion, scale and weight. This is why we need subwoofers even for full-range speakers, as these subsonic frequencies must have higher amplitude than the center midrange frequencies that we take as a benchmark for ear. If you think about typical 80dB SPL, then to achieve the loudness equal to 80dB@1kHz, the low end must be boosted to around 95dB@40Hz, 110dB@30Hz, and so on… Usually, the mixing and mastering engineers take care of it, yet some of the energy can get lost in your room. That’s why we employ subwoofers and/or DSP to tackle the problem.

However, the ear has a wonderful ability: it can reconstruct the fundamental frequency (pitch) through the frequency harmonics. So, even if your system cannot play 41.2Hz, it probably can play 82.4Hz, 123.6Hz and 164.8Hz. Hearing the harmonic structure of the fundamental note is what makes up for the lack of bass fundamental. Vinyl lovers and bookshelf speakers’ owners are saved, or at least the playback is a good approximation of what a full-range system can play, save for the subsonic ambiance and sound envelopment that will keep missing until the array of perfectly phased subs is employed.

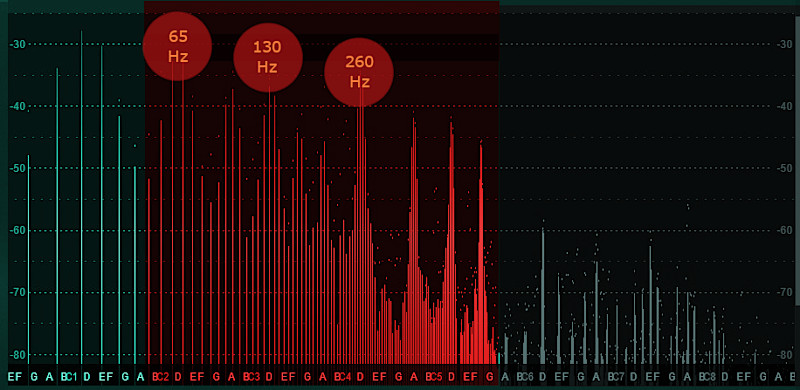

In the picture as above (energy spectrum of the bass on No Sanctuary Here´s initial tones), one can see the red part, which is the instrument’s bass fundamental and its harmonics. The blue bass is coming from the interaction of the instrument and microphones with the room.

The world of bass adjectives

To describe the quality of bass sounds, an ever-expanding vocabulary is used. Some terms are technical, some very poetic, yet all make sense. Out of all, the “good bass balance” is the trickiest expression, as what is balanced for one person, can be out of balance for the other. But other are more intuitive.

The dry bass usually lacks bloom, richness and expansiveness. The former two inefficiencies are the result of insufficient extension, suppressed harmonics and overdamping, the latter is the result of missing low-end ambience, so the sounds miss the spatial clues. I am not saying that having dry bass is good or bad – the dryness fits some music very well. It is all about artistic intent.

The articulated bass is easy to follow. The bass has a good transient snap, it has speed, visceral power (the pressure felt by body) and slam, and there is no hangover and smearing. Interestingly, the articulation of the bass is often achieved by severe shelving, cutting, equalization, and compression in the production process. The ‘articulated bass’ can, however, also indicate that your system or the room (or both) introduce deep dips in the frequency response. One of the best examples I can give is the “Tight Bass” setting of the SPL Audio Vitalizer MK2-T that introduces up to -15dB (!) notch in the frequency response centered at around 50Hz, affecting with its Q the frequencies up to 150Hz. Translated into plain language: lack of bass on certain frequencies may lead to more articulated bass spectrum as a whole, without losing the weight and size.

As much as the articulation is a good thing, overdoing it means that the bass becomes lean or thin. And as much as the deep and fat bass is a good thing, it may lead to muddy, boomy, dull or loose playback. Selective imbalances and resonances can introduce boxiness or chestiness and make the sound coloured.

In the end, I am back to the “good bass balance”. Aside from personal preferences, there are many parameters that must be balanced to achieve textured, dynamic, articulated, expansive and yet really deep bass, that shakes the room with control and wraps around the listener, and that is beautiful. And, as already said, room dimensions and loudspeaker placement within the room are absolutely critical, as well as the recorded material that is used.

What does this frequency do?

The options for an audiophile are somewhat limited vs the relative freedom of a studio engineer. What we get is the complete mix, mastered and ready to play, as the artist/studio wanted it. Which is often not how we want it. There are no limits to your creativity and if you want, you can add a parametric equalizer or a complete mastering chain between you source XLR outputs and your amplifier XLR inputs. If your playback chain is fully digital, then it is even easier, and plug-ins will do the job for you. Equalizing a recording in the playback chain is a bit of road to hell, as from that moment on you will become obsessed by tweaking every single album (or a song) to perfection. I can say so from my own experience. To acquire a simple equalizer (be it graphic or parametric) is the easiest way of experiencing what can be done for the bass or any other range. The basic 31-band devices like dbx, Behringer, Klark Technik are cheap. Playing the song through that equalizer and moving one frequency band slider at time slowly up and down will tell you in which direction it affects the sound. Then you can combine two or more sliders. Also remember the rule of harmonics, so you may tweak twice or thrice as high in frequency to achieve the best result. For instance, if the boost at 80Hz sounds good, you may also slightly boost at 40Hz and 120Hz.

The main problem of this “mastering the master” approach is that we will always work on the complete mix, not on individual instrumental tracks. And because no one instrument is alike, tweaking a guitar to perfection will unpleasantly colour vocals or kill until now perfect kick drum sound. Everything is linked in one way or another and without separating the instrumental tracks the result will be always compromised.

The suggestions of mixing and mastering pros (below) will give you an idea about what studios do to equalize the bass part of recordings:

20Hz and below

Remove completely, as it only adds unnecessary energy to the total sound that is not needed and overloads amplifiers and speakers.

40Hz

Crush most bass below 40Hz with high-pass filter to remove bass boom and mud and improve the clarity of mix.

Cut -8dB below 40Hz to remove the low-end rumble from bass guitar and make it more articulate. If you want to hear the string snaps of the guitar better, you need to look at around 2.5kHz.

50Hz

50Hz is the nominal frequency in the power grid (Europe), as well as the frequency of the ground loop.

Cut below 50Hz on all vocal tracks to reduce the ‘pop’ sounds from the microphone.

50-60Hz - boost to thicken up bass drums (kick drum) and subwoofer parts.

60Hz

This is the area where the heavy punch (kick drum, toms, bass guitar, hip hop groove) starts. Boost to bring out the thud of the kick.

A male voice can reach down to 70Hz, but most of its definition lies in the midrange.

80Hz

60 to 100 Hz is where the kick drums provide the most of "the punch that can be felt in your chest".

Boosting adds warmth and fatness to bass lines. Too much boost sounds boomy.

82Hz (second harmonic) is where the most energy of the bass guitar is (like in No Sanctuary Here).

100Hz

100-120 Hz is where the "club sound system punch" resides.

100Hz is also a good point to add a broad shelf for entire low-end that sounds musical (typically used in tone controls).

100Hz also adds the bottom end to piano and fullness to snare drums.

120Hz

Add +4dB at around 120-130Hz for fuller sound of electric guitar. Too much makes the guitars boomy.

Another trick to add growl to electric bass is to boost around 600Hz, or around 800Hz for definition, or around 4-6kHz for string slap.

140Hz

Body and meat of drums. The transients of drums usually reside somewhere in 1.5-2.5kHz area.

Adds warmth to singers.

160Hz

164 Hz is a harmonic of the bass guitar’s fundamental low E note, 41.2Hz. Boost for extra clarity.

Too much makes the mix cloudy.

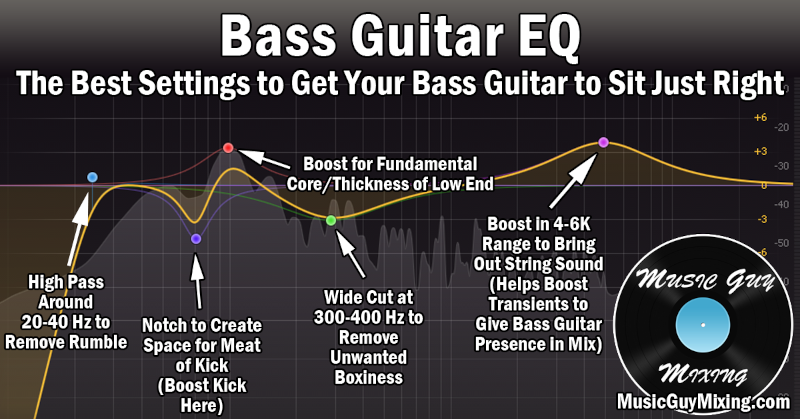

One of typical EQ curves for the bass guitar may therefore look like this:

Conclusion

The purpose of a good hi-fi system is to reproduce the music material as it was recorded (not as it sounded live in concert or a studio). Although there are recordings that do not use any overdubs and postprocessing, there are hardly any that do not use any sort of EQ or compression. For the purpose of reproduction, playing with equalization (like DSP or hardware EQs) compensates for acoustics-related problems or gear-related problems. It also can help improve final mixes, but it is important to realize that improving the fatness of the bass can throw e.g. the piano ‘out of balance’.

There is one learning though: next time you marvel at the super-deep bass at a hi-fi show, and before you invest into another subwoofer, think twice about what you are hearing, and which part of the frequency response is responsible for what you are hearing. The deep bass is much higher in frequency range than we think.

(C) Audiodrom 2024