TAD Revolution One / Part 5 - FinAle

This article is the last part of the Revolution One project story. At the time of this write up, 16 months have passed since the Evolution Ones were removed from the room and their crossovers were dismantled. It means finishing the project half a year later than expected. On this opportunity, I would like to look back and make a fair assessment whether the project has reached the goals and, ultimately, whether it’s been worthwhile at all.

TAD Revolution One / Part 1 – Cabinets

TAD Revolution One / Part 2 – Crossover

TAD Revolution One / Part 3 – Crossover parts

TAD Revolution One / Part 4 – Casework and fine-tuning

TAD Revolution One / Part 5 – Finale

Recapitulation

By eliminating the empty space within the atoms constituting the human body and bringing them closer together, a remarkable compression can be achieved. This compression would allow the entire human population to fit within the confines of a single sugar cube. This is a scientific fact. One of the ways of looking at it is the realization that the human body is mostly… an empty space.

In the Revolution One journey, there were certainly good moments, and we were building the new crossovers, atom by atom. However, most of the project’s time continuum consisted of empty space. There were weeks of waiting for parts, weeks of breaking in the parts. In the final stage of the design, some parts already had about 800-1000 hours of music on them, but each of the latest finishing adjustments to the crossover required to be properly broken in for at least days before we could assess whether the change was for good; if not, we needed to repeat the process again. And then often once again. This waiting emptiness was necessary evil, a tax paid for building the final atomic structure. The landmarks can be summarized followingly:

- The TAD’s cabinets have been improved structurally as well as aesthetically. From each, the 3-piece crossover network has been removed, and the plinth’s interior has been rebuilt into a non-resonant structure that now anchors the speakers with increased mass and lowered centre of gravity. The speakers have been finished in deep gloss.

- The new crossovers have been simulated, designed and finalized from premium parts. There are 41 components in each channel, out of which 22 are Duelund (18 capacitors and 4 coils), 9 are Jantzen (6 capacitors and 3 coils), 6 are Mundorf (1 capacitor and 5 resistors), and 4 are WBT (binding posts). Should you wonder why so many capacitors, please note that for some critical ones we used cascades of smaller values, because it sounded better.

- AAI wires and AAI hardware are used throughout the project. Almost all components are connected by their own leads, no hook up wires, with 2 exceptions for Duelund bypass capacitors as their leads could not embrace their own oversized Duelund caps. There short runs of braided pure silver wire are used. The AAIs connect the binding posts with the nearest crossover’s entry/exit point.

- The CNC-milled casework has been built rib by rib and assembled by Silent Laboratories, who also supervised the whole technical part, and implemented many smart improvements in it.

Building transparency

”When a song is finished, the real working process begins because I'm almost morbidly intent to achieve absolute transparency in a sound picture. I think everyone listening to my music should have the opportunity to step into a three-dimensional sound world. That means meticulously separating all frequencies so that nothing interferes.”

Boris Blank, June 2014

For transparency, absolute phase alignment is imperative. Therefore, this parameter was pursued with almost fanatical commitment. As far as the frequency response was concerned, I did not care about it too much; the goal was to achieve the good overall slope (I wrote about it in one of the previous parts of this journey); the room-induced peaks and dips did not bother me for those had been fixed as much as possible by acoustical treatments in the past. The phase was a different animal. No compromise there, as I could hear how devastating was not getting it exactly right during another project of ours, the cost-no-object modular Equilibrium speaker tower system. Hairline offsets of drivers in any direction made huge difference and there was always just one optimal position. Simulations and measurements were of no use, for these hairline adjustments never projected into what we could see on the screen. Our ears were much more discriminative so there was no other way than listen through the changes and assess the results.

Of course, we could not change the way the drivers were mounted in the cabinet, but we could move the drivers back and forth virtually by adjusting RLC parameters in the crossover. Although we optimized this in the final stage of the crossover optimization process, we had to do it again - once the speakers were repositioned in the room, and once the crossovers were assembled and closed in their cases, and once the cases got in the proximity of other electronics, the interacting electromagnetic fields inevitably shifted the nominal values of some crossover parts.

In fact, while some of this interaction was destructive, other was constructive. In an egoistic project like the Revolution One, we had luxury to readjust everything for my particular preferences. And, as mentioned, there was no way to simulate these subtle shifts - I had to spend weeks by doing this fine-tuning job. It was not unlike assembling a Rubik’s cube. Six faces with six colours, nine segments each, and only one combination that is right. Various moves, many errors on the way. I spent about netto 40 hours spread across several weeks to get the crossovers “in the absolute tune”.

The phase puzzle had to take in account other ‘acoustic’ accessories that manipulate the harmonics and the way they are heard. So, along with the subwoofer, feet, and cables, I needed to take resonators for the ride as well. My room uses more than forty of them - Synergistic Research HFTs and Black Boxes, Stein Music H2 Harmonizers, and ASI Sugar Cubes - and I had to recalibrate most of them. Bad news was that they interacted so while readjusting H2s, I was messing up with the benefits of some e.g. HFTs, and vice versa. Thus, I had to work with many variables, a network of mirrors that connect to each other via correct placement and correct angles as I described it the review of the Stein Music H2. Although all these accessories work in ultra-high frequency domains, they have the power to influence the whole audible spectrum, and one or two stupidly small wooden cubes can affect the weight and definition of bass, for instance. As they make every little disbalance even more audible, the last tiniest imperfections were revealed and corrected.

The raw Revolution One crossovers were installed at the beginning of June, and we achieved a reasonably high level of satisfaction towards the end of August. All this time my audio set-up was basically playing nonstop, soft or loud, to burn the parts in. When I mentioned what I was doing to Robert Slowinski of Next Level Tech, who had some experience with Duelund parts, he warned me that I would need “a thousand and more” hours to hear what they could do for sound. He was right. If you consider the amount of metal and the mass of dielectrics in these oversized coils and capacitors, they definitely take some time to format. My estimate is that the bass settled down at around 500-800 hours of music, the upper frequencies got complete at around 1200 hours.

Another month have passed since August and while continuing with the burn-in process, I used the opportunity and revisited the crossover feet. I tried IsoAcoustics Gaia II feet under the cases, mostly lured by their appearance, but not only – the IsoAcoustics performed great in the Equilibrium project as well as they are go-to feet for Marten speakers that I regard high. Unfortunately, they did not work under the Revolution One crossovers and made the bass spectrum muddy and hollow. AAI Estremo stayed there, and AAI feet confirmed their supremacy also in other positions under electronics and cables. Neither did revision of power cables bring anything new. For whatever reason I felt an urge to replace the main power cable in the system by Synergistic Research’s SRX (perhaps that it was so good performer in other systems?); after spending few weeks with it I decided that the existing combination of Ansuz Mainz C2 and AAI Maestoso provided far more balanced and mature sound. I also challenged Ansuz C2 interconnect between the source and the amplifier. I had tried to push it out in the past with SR SRX, Nordost Valhalla 2 and Odin, Ansuz D2, AAI Assoluto, Stealth Metacarbon, and AudioQuest Thunderbird and Dragon - with no success. Therefore, to make a real jump, I borrowed the amazing Stage III Concepts Ckahron. Considering the drastic price difference, the Ansuz C2 stays for the time being, yet I plan to revisit this subject again.

So, the sound of the system was morphing into something truly remarkable, and the listening experience got transformed from a high-end presentation to natural ease and flow of music. All the steps made in this fine-tuning phase were reversible and therefore I could always go one step back to validate that the progress was a real progress, not only a momentary excitement. Step by step I achieved the point when I could not stop listening and then, when the last song ended, I said to myself: „My God, this is it—don't screw it up!'

Tactile bass

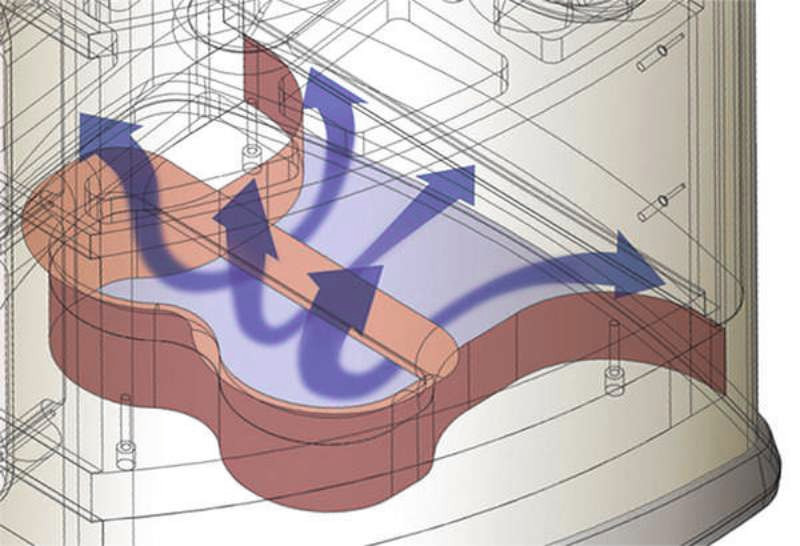

I must acknowledge one possibly deficient feature that we could not do anything about: the presence of the bass reflex port. TAD Evolution One is vented through the channel that opens to a flat shaped front-firing waveguide. It is a smart solution to improve bass efficiency while maintaining its good quality, and the bass has weight and power without any artifacts that are often associated with round bass reflex ports.

Yet, the very presence of the port means that the phase relationships in bass will always be out of tune around the area of the port’s tuning (31Hz). For sound, it means that it is impossible to achieve the alignment of closed speakers. I had to accept it. Still, this is a minor quibble as with the new crossover the Revolution One´s bass has become by big margin better than the Evolution One´s. In fact, it is one of the areas that benefited the most from the crossover redesign.

So, what’s the bass of the Revolution One like? When I listen to well-recorded tracks, I am in heaven. Charly Antolini’s dynamic percussive pieces have the power to shred me in the listening chair, and the hits of the big drums of Akatsuki (as found on a Stereoplay sampler) are like bombs being dropped in the room. Electric bass has low-end explosiveness, energy, and heft, as well as tons of textural detail, and it can be often traced back to the electric hum of a bass amplifier.

But that is not everything. There is a parameter that has acquired almost supernatural quality and that was not there with the Evolution One: the start-stop behaviour of the system. What do I mean by that? Imagine the moments when a low-frequency transient pulse sends a bass cone into its maximum excursion and immediately after that the membrane is damped into digital zero silence again. The sound blasts from nowhere and ceases to exist in a millisecond again. There are albums that are generous with such moments, like Borise Blank’s Electrified, or The Dark Knight soundtrack. Not the vinyl versions, of course, they cannot compete with the precision and slam of the digital masters. Such laser-cut deep pulses let the new TAD Revolution One excel. Blank’s Key Largo is a good example - the bass line detonates from the speakers, penetrates through my body, and then stops in a single frozen moment in time. There is no decay, no momentum of sound, the sound is just there in full power and then there is nothing, suddenly. The sound stops so abruptly that I am almost ballistically sent forward from my listening chair in expectation of continuation. It is as if I hit a concrete wall in full speed. Any genre benefits from the ability to control the speakers with no electric haze, no phasiness, and no smear, but the electronic music with sharply defined transient pulses shows it off in the most fascinating way.

Concert levels

The Evolution Ones were always good in illuminating the tiniest details in recordings and the Revolution Ones have improved it to perfection by dropping the inherent noise levels using superior electronic parts. The recordings that were originally made on tape now enable tracking the decays until the details sink in tape hiss. On top of that, I can track individual profiles of different tape hisses belonging to different instruments or voices in multitrack recordings. With digital recordings, the ambience of a studio or a concert hall is now more palpable, so are rustling music sheets or squeaking floorboards. The Revolution One waits until all the sounds trail off and then tells you - listen, there is hum of electronic circuits in a guitar amplifier, ground loop in an analogue synthesizer, or crackling of a tube in a microphone. Although such noises are not a music strictly speaking, they make listening so authentic as I am able to track the recording tracking.

Good acoustic music recordings have achieved a completely different level of clarity with the new crossover in place. Not only can I hear deeper into music, but I can also use volume control as a magnifying glass too, with seemingly no upper limit. On other occasions, I mentioned that as my audio system (and acoustics) was improving over the years, I could listen louder and louder. Still, there was always a loudness point beyond which the sound got congested and it was not enjoyable anymore. It was just too much for the speakers to handle. Now this limit has been gone. I can play as loud as I want, and the sound stays under control and is perfectly legible and not tiring at all. There is other side of coin to it – the listening sessions become dangerous. It often happens to me that after I listen to music for couple of hours, I leave my listening room with too much pressure in my ears, as if I was leaving an AC/DC concert. With rock music I have no benchmark for loudness, it is a matter of momentary preference; with acoustic instruments I try to set the loudness as ‘real’; a double-bass or a violin should not be played much louder than a double-bass or a violin playing live in a room. Vocals are also a good guideline. With the TAD Revolution One I cannot have enough of vocals. They are so nuanced, sweet and finely articulated, that they are truly breathtaking. This sweet delicacy is addictive, and I am spending many evenings going through thousand titles in my collection to listen to various vocal performances again. There is always something new to explore even in the recordings that you think you know intimately; it is fascinating how such a sound upgrade makes you re-listen to everything you own. With sentiment, I recollect old days when I only had around thirty albums and played them over and over again. The re-listening job was so much easier, wasn’t it?

Beauty of tone

In retrospect (and as described in the previous parts of this journey), the original Evolution One has the tendency to highlight the upper midrange part of spectrum. Thus, together with some lift in the ‘air’ region of treble, the Evolution One behaved like revealing studio monitoring gear. Yamaha NS-10 comes to my mind. This two-way sealed-box speaker was launched in 1978, and yet did it fail to succeed commercially, it earned amazing reputation among sound engineers for its ability to reveal shortcomings in recordings. It featured two drivers, a 180mm paper pulp woofer and a 35mm fabric tweeter, crossed over by 2nd order network.

The NS-10’s sound had boost in the upper midrange (+5dB boost at around 2 kHz), which led to very open and detailed sound. As human ear is very sensitive in this area, any recording disbalances were easily heard. Notably, the NS-10 had excellent impulse response, thanks to the closed box design, thus its transient handling was superior to the most of monitors available on the market at that time. There is always the other side of the coin, though. In the case of the NS-10, the very same presence that made the speaker so detailed was its Achilles heel: it was tiring to listen to.

For the Revolution One, we’ve made deliberate decisions to sculpt the frequency response the way I wanted. Another quick decision (accept or not) must have been made when we arrived at the resistor-free signal path that shifted the balance of midrange in favour lower mids, and the sound became fuller and denser. I did not want to have the sound dense too much so that it would lose the vibrancy and excitement. On one hand, I was a little worried whether I would hear what I was used to hear with my usual playlist, on the other hand, I was curious how it would sound after the upgrade. Often, I use Vilde Frang´s rendition of Korngold and Britten Violin Concertos (Warner Classics/Parlophone) for the transparency, tonality, and imaging test. It is a purely digital recording with rather introvert masterpieces, played on Jean Baptiste Vuillaume´s copy of the 1716 ‘Messiah’ Stradivari, which Vuillaume owned and has been copying for business two centuries ago. The instrument has a beautiful tone and Frang has superb intonation, and both shine through the closely miked performances that capture the dynamics of her playing. But there are other captivating moments, like timpani ushering the 1st movement of Britten’s Violin Concerto, Op.15, followed by lyrical interplay between the violinist and the orchestra. The Revolution One provided me with unadulterated sound with dramatic dynamic sweeps, quick transients and absolutely clear outlines of the notes. The timbres were textured and lifelike. Me in the studio. Good balance. Midrange approved.

Holographic purity

When Jan of Silent Laboratories measured and compared the original RLC parts that had been used in the left and right crossover of the Evolution One cabinets, he found some values fluctuating by as much as 10% and more between the channels. The new parts are closely matched. By removing the asymmetry, I have been able to focus the speakers and have got a sweet spot that provides impressive soundstage with fascinating spatial resolution. It is not anymore about left/right and front/back, it is recreation of recording session events. Swan Lake played on two pianos (Accuphase SACD sampler) is a typical torture test that I use for spatial resolution and perspective. Both pianos should be distinct and separated in space, you should be able to hear where the hammered strings of each piano were in relation to each microphone, you should be able to hear distinct noises generated by the interaction of each player with the mechanical systems of the instruments. On top of that, the track should be natural, depth of image should not be bloated nor constricted, and definitely it should not sound like an overhyped audiophile showpiece.

The TAD Revolution One not only does offer me an immersive look into a black mirror that reflects the recording sessions, but it lets me to deep dive into it. I’d like to have a bigger listening room to achieve a grander scale of especially symphonic and rock recordings; when it comes to the rest of what I listen to, I can hardly dream of better sound.

In the past, I’d put a lot of hard work in the room’s acoustic and into minimizing crosstalk of speakers, long time before I started to rebuild the crossovers. I’d put also a lot of hard work into as low background noise as possible, including quite complicated power conditioning and grounding scheme. Perfectioning the phase relationships between drivers was the last drop. The way I am a part of the soundstage reminds of my experience with Theoretica BACCH processor, as demonstrated to me by Edgar Choueiri and David Chesky. The Revolution One of course cannot replicate the complete crosstalk elimination like the BACCH does, yet their meticulous paring manages to remove the room very successfully. The multi-miked instruments are a good example: the Revolution One let me hear the phase relationships as they were downmixed from two or more microphones, that were ‘bleeding’ into each other. Again, it has nothing to do with the music as such, it is a bonus that allows me to see into the creative process of the recordings’ sound engineers.

When I was finishing last paragraphs of this write up, I dug out my notes, several bullet points that I had made about how possibly the Evolution One should ideally sound after the crossover redesign.

- I wanted it to sound beautiful. Although ‘to sound beautiful’ is not a static parameter due to its subjectivity, I know what I meant by it. Sweet transparency was another term I noted down. The sound that is luxurious, dense in colours, dynamic, firm, crisp and clear, and magnetic. The sound that I am unable to "take my eyes off".

- I wanted deeper soundstage. I would not say that I have radically deeper soundstage compared to what I had before. However, the soundstage of the Revolution One is much more palpable, almost physically 3D, and imaging is insanely accurate.

- I wanted to reduce the slight forwardness in the presence region, and add more weight, punch and slam in the bass. Apart from the phase-related improvements, I believe much better bass control and shaping the balance between midrange and treble greatly contributed to it.

- I wanted not to lose anything else. I did not want to lose transients, air, and the playback coherence that the Evolution One did exceptionally well. This part was the most frustrating one as it was not easy to rebuild all these parameters, but we’ve succeeded in the end.

Has it been worth it?

It depends on the angle of view. In terms of sound improvements, the answer is unequivocal yes. The TAD Revolution Ones sound so terrific that I yawned all through the audio show I have visited recently. However, there is no limit in audio and if we could get such performance from inexpensive speakers, what could we get from rebuilding e.g. a Magico?

Applying another angle of view, has it been worth it financially? If I only consider the material costs, they have added 50% to the price of the Evolution Ones when they were new. Check the prices of the parts and you will know why. On top of that, there was a lot of specialized work, preparations, brainstorming sessions, consultations, simulations, drafts, measurements, and more from Silent Laboratories, AAI, Duelund, and Jantzen, Finally, a lot of time put into assembling, re-assembling, burning in, re-burning in, corrections, listening room and audio set-up recalibrations, all accumulating in hundreds of hours. Now I understand why some audio manufacturers charge so much for their products; if you don’t take shortcuts, then perfectioning a product and validating your engineering approach is an expensive process. Well, we tried not to take shortcuts with the Revolution One and took it a bit to extreme. If I’d accepted compromises, it could have been a nice and funny project for 3-6 of months.

If I had sold (at a loss) the Evolution Ones and had bought (at a discount) one of the overpriced speakers I mentioned earlier in this series of articles, would that have been more financially interesting than rebuilding the TAD and have the same performance? Unfortunately not; I would have to spent another 15-20k€ on top of what I’ve spent on this project. So, if you are not the type of audiophile that sells and buys speakers every year or two, and if you want to build something unique and unparalleled sonically, go for it. Feel free to contact Silent Laboratories or any other expert who knows what to do.

Speaking of Silent Laboratories, I would like to thank to Jan Mixa for his indomitable optimism and firm faith in the result. In the moments when I was sinking in my mind because I couldn't get the sound where I wanted it to be, he always had some more ideas in sleeve for what to do. The fact that it turned out even better than both of us expected is mostly to his credit.

The list of components that were used for final fine-tuning of the Revolution One:

Sources: Accuphase DP-720 SACD a Accuphase DP-770 SACD, xDuoo XT10T II digital player

Amplifiers: TAD M2500

Interconnects and speaker cables: Ansuz Signalz C2, Krautwire Numeric, Stage III Concepts Ckahron, AAI Maestoso, AudioQuest Dragon Zero |Bass

Power conditioning: Shunyata Research Denali 6000T, Stromtank S-1000, Ansuz Mainz C2, Stage III Concepts Kraken, AAI Maestoso, AAI Assoluto, Synergistic Research Atmosphere Level 2, Synergistic Research SRX, Nordost Qv2, QWave a QSine, Diamond Sound Ground Units

Useful contacts:

Silent Laboratories – Jan Mixa, +420 777 772 642

Authentic Audio Image - AAI - +421 905 694 943

TAD Revolution One / Part 1 – Cabinets

TAD Revolution One / Part 2 – Crossover

TAD Revolution One / Part 3 – Crossover parts

TAD Revolution One / Part 4 – Casework and fine-tuning

TAD Revolution One / Part 5 – Finale

(C) Audiodrom 2024